Sheikh Waheed Baksh

Dhara Mungra

Veer Pariawala

Raghav Jain

Apon Das

Manisha Biswas

Fowzia Afroz

Aditya Surve

Subinoy Mustofi Eron

Shahzeb Mahmood

Swapneel Mehta

Shoeb Abdullah

In recent years, the digital realm worldwide has been marred by the pervasive occurrence of technology-facilitated gender-based violence. UN Women defines this phenomenon as perpetrated with the use of digital tools to cause harm to women, girls and other gender-diverse communities based on their gender and sexual identities. Such violence manifests in acts such as intimate image abuse, doxing, trolling, online stalking, sexual extortion, and the sharing of non-consensual deepfake images.

In Global Majority regions, including in Bangladesh, the digital sphere has evolved into a critical arena for political discourse, resulting in confounding consequences at the intersection of gendered attacks online and democratic processes. Gendered attacks are weaponized to harass and target political opponents, journalists and activists, deterring, and even restricting, the political participation of women and gender-diverse communities.

Our study initially aimed to unravel the intricate dynamics of technology-based gender violence on Facebook in Bangladesh, particularly in the lead-up to the country’s general polls in January 2024. However, applying established disinformation methodology to the country’s political context posed several challenges. The highly diffracted information ecosystem, coupled with opaque and multi-partisan allegiances on social media platforms, made it extremely challenging to identify the sources and targets of malign narratives in Bangladesh. Another confounding factor was the lack of consistent definitions on abusive terms. Historically, defining “abusive terms” relied on cybersecurity lexicon and natural language processing of American case law, and does not directly translate to the experiences of women, gender diverse and vulnerable communities in Bangladesh and Global Majority countries.

As a result, while disinformation studies worldwide have explored online gender-based violence, our study specifically aimed at:

Our hope is that this study can provide a starting point to not only better quantifying harmful gendered abuse in Bangladesh and their impact on civic participation, but also a context-responsive framework for investigating technology-facilitated gender-based violence (TFGBV) in Global Majority contexts.

According to one study, 58% of young women and girls globally have been sexually harassed on social media platforms. A joint study from the Bangladesh Legal Aid and Services Trust and BRAC estimates some 66% of women and girls in the country have experienced cybercrimes. ActionAid finds that 64 out of every 100 women and girls in Bangladesh have experienced some form of online harassment and violence. At present, there is no nationally representative public data on TFGBV in Bangladesh.

UN Women’s findings underscore that technology-based gender violence not only causes immediate harm but also exacerbates offline forms of violence, ranging from sexual harassment to trafficking. In the context of elections, this takes on unique significance as digital tools become instrumental in profiling, recruiting, controlling, and exploiting victims, potentially influencing political dynamics.

Data from the Institute of Development Studies and the Economist Intelligence Unit reveal a significant percentage of women experiencing technology-facilitated gender-based violence. The most prevalent forms — misinformation, cyber harassment, hate speech, impersonation, hacking, stalking, astroturfing, video and image-based abuse, doxing, violent threats, and unwanted explicit content — indicate a pervasive issue that demands attention as Bangladesh navigates a fraught democratic landscape.

On top of gender-based violence, misinformation (i.e., false statements of facts) and disinformation (i.e., deliberate spreading of false information that suggests maliciousness) pose additional threats to political involvement and the societal standing of women and members of the gender-diverse communities.

Women’s political participation remains low in Bangladesh despite the leadership of two female prime ministers for most of the past five decades. Article 65 of the Bangladesh Constitution stipulates that the country’s unicameral parliament shall consist of 300 constituencies, each elected through direct ballot. However, an additional 50 parliamentary seats are reserved exclusively for women, based on proportional representation.

While this measure has been implemented to encourage women’s participation in national politics, it has primarily been seen as a symbolic gesture. In the last national election, less than five percent of candidates vying to be elected as MPs through direct ballots were women. The trend is consistent across different layers of the local government as well. Politicians and observers often decry the lack of level playing fields for women candidates and those from gender-diverse communities.

Historically, Bangladesh’s political landscape has been marked by a tumultuous atmosphere of street battles, agitations, and protests. Within this environment, partisan activists climb the party ranks predominantly through engaging in street politics — a realm that, by its nature, tends to favor men over women, thereby contributing to the pervasive male dominance within the hierarchies of political parties.

Additionally, conservative cultural and societal norms discourage women from pursuing political engagement. Gender-based attacks targeting female politicians’ competence, supposed moral character, bodily appearance, religious practices, or personal behavior have proven to be significant obstacles to women’s participation in democratic processes.

Thus, those who participate in civil and political activities defying existing barriers often face an exacerbated risk of abuse aimed at silencing their voices and humiliating them in the eyes of the broader male-dominated audience. However, this study on the proliferation of harmful gender-based content targeting prominent Bangladeshi public figures on Facebook found that men can also be targeted with such language on a large scale, especially in politics, activism and journalism.

Even before the advent of social media, established female politicians endured sustained attacks on their character and behavior. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, for example, has long been the target of false information campaigns alleging that she was a Hindu, having secretly married a former Hindu aide. Several iterations of this disinformation still circulate on social media today. Khaleda Zia, the leader of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), was subjected to a sustained campaign by government officials and pro-ruling party news outlets claiming that pornographic materials and alcohol had been found in a house from which she was evicted.

In Bangladesh, societal and official views predominantly support binary notions of sexuality and gender — a pattern that itself poses significant challenges for individuals with diverse gender identities, which are often seen as taboo. Despite some progress, such as the government’s formal recognition of a “third gender” category for hijras (e.g., transgenders) in 2013 and their political participation in 2019, these communities still face stigma and derogatory treatment. For example, the acknowledgement of hijras, while a step forward, has not prevented the abuse of LGBTQI-related terms by some political entities to disparage their opponents. Facebook Pages that appear to explicitly support the ruling party’s objectives and political mission often employed the terms “hijras” (transgender) and “samakami” (gay) as derogatory slurs against their political opponents, activists and journalists.

Coordinated disinformation networks on social media and self-acclaimed online news portals have just added another layer to this existing problem. While the most influential politicians are often expected to mobilize large crowds in street demonstrations, notable female politicians have found their strength in engaging with the public through smaller organized gatherings, serving as party surrogates on popular media channels, and leveraging social media platforms. Their visibility is more pronounced when delivering fiery speeches than leading street demonstrations. As a result, the increasing prevalence of attacks against them on social media poses a significant obstacle, which threatens to narrow the already limited avenues available for female politicians to make their voices heard and engage with the public.

We find that while for women, harmful language can be rooted in expectations about their behavior, appearance, and societal roles, men are compared to “হিজড়া” (transgender) or homosexuals as if they conveyed the lack of masculinity, shame and stigma. Among the analyzed content, prevalent themes included derogatory language with sexual undertones (e.g., body-shaming, verbal abuses, and attacks on gender, religion and sexual orientation) targeting politically and socially notable individuals, and unwarranted exposure of personal information or images (e.g., exposing the target’s alleged sexual orientation and private organs).

Our research highlights that while the backgrounds of male targets are varied — from politicians and journalists to social media commentators, influencers and activists — female targets are overwhelmingly politicians, especially those from the political opposition. These attacks threaten to limit their online presence and contribute to a broader chilling effect, dissuading potential female candidates, activists, and voters from actively engaging in the democratic process. The use of stereotyped language to attack men also deepens gender-related stigma and polarization, which will have repercussions for the country’s democratic and societal cohesion.

Note: This section includes references to explicit keywords and strong language. We decided to include them in the interest of transparency and replicability and to underscore the challenges in conducting external research into Meta’s datasets.

We relied on the CrowdTangle UI and API to gather data from Facebook Pages and public Groups. The dataset we compiled does not include content posted by individual profiles, as CrowdTangle’s API restrictions prevent the collection of posts or comments from individual users.

Given that our research exclusively focuses on coordinated campaigns through the actor-level investigations on Pages and Groups, it might not fully capture the broader social dynamics of gender-sensitive abuse directed at notable figures, women or marginal communities online.

Instead, our research represents a first-of-its-kind effort to gauge efforts by seemingly organized networks employing and amplifying gendered abuse as a propaganda campaign to silence or undermine their political targets.

In our study, we developed a Bengali corpus featuring “hateful keywords” — e.g., derogatory slurs — and identified “targets,” such as male and female politicians, journalists, social media influencers, and activists involved in social and human rights issues. This list is extensive and represents a broad spectrum of potential targets, drawing on our prior research, preliminary tests, and expert consultations. In establishing the list, we find that a standardized set of slurs, even translated to multiple iterations of the Bengali language, does not necessarily correlate with the range of abuse that women and gender-diverse communities experience. On the contrary, the gendered attacks are often highly relational, asymmetric, and use innocuous terms.

We incorporated various iterations of Bengali, Banglish (combination of Bengali and English commonly used in informal communication) and English terms and names to ensure a wide range of captures in our data collection. After refining the list with input from domain experts, we applied it to collect all public posts and their interactions (e.g., reaction counts) from Facebook Pages and Groups between December 1, 2022, and January 15, 2024.

We applied the ABC Disinformation Framework, originally developed by Graphika and the Berkman Klein Center at Harvard University but ran into several challenges related to the differential information ecosystem in Bangladesh and the Global Majority.

As a result, actors are harder to identify with confidence, behaviors are varied and interspersed with large volumes of benign interactions and online activity, and content is challenging to isolate using existing practices including keywords, context, narrative-identification, and coordinated network analysis.

Instead, we employed a human-in-the-loop approach to intensively vet a set of hundreds of harmful keywords and their oft-misspelled variants that are context-specific and iteratively updated based on preliminary data analysis, in order to identify the key narratives, sources, and targets of hateful speech and online harassment. We found that the standard corpus of harmful words, including slurs, were insufficient to capture the varied nature of harassment, and applied a set of highly contextual and relational keywords to establish more representative parameters. It serves as a model reflective of the nuances inherent in identifying online harms in an important Global Majority context relevant to democracy.

With the new set of parameters in place, our preliminary search returned 23,047 entries, each corresponding to a post matching our criteria. However, posts can contain multiple keywords and targets, so we identified duplicates within this initial dataset. Removing these duplicates left us with 12,287 unique entries.

Our analysts then individually rated each of the 12,287 posts and determined that over 1,400 of them featured gendered attacks, including instances of misinformation and disinformation.

Our analysts employed a specific secondary set of criteria to assess whether a post constitutes a gendered attack.

Posts were identified as gender-based attacks if they involved verbal assaults aimed at individuals due to their gender, sexual identity, or orientation. This classification spans a spectrum from character defamation to threats of violence, thereby expanding the slurs-based approach to reputation-based damage. Analysts also considered derogatory and contextually salacious comments about an individual’s physical appearance, lifestyle choices, inhuman comparisons to animals, and attacks anchored in religion, ethnicity, or other protected characteristics. We further included keywords to detect a specific set of gendered expectations of societal behavior that is used to harass and target women and gender-diverse communities.

We adhered to a rigorous, human-led verification process to identify misinformation or disinformation, utilizing analysts with professional expertise in conventional news fact-checking. They assessed the authenticity of content by consulting only reliable news outlets and established fact-checking tools. Specialized search techniques were employed to trace the sources of information. Content deemed incorrect or fabricated was labeled as misinformation, while material aimed at deliberately damaging political adversaries through misleading means was marked as disinformation. Fact-checkers also took into account the historical behavior of the actors (e.g., Pages, Groups and users), including their transparency records, in their evaluations.

Our analysis of 1,400 gender-based attacks reveals they mainly echo 300 original posts or their variations. The repetition of the same texts or posts across multiple Pages or Groups points to an organized effort to disseminate misinformation and disinformation.

Our findings reveal that up to 70% of 1,400 abusive posts involve unfounded sexual insinuations, such as accusations of being a prostitute or allegations regarding sex tapes. Another 18.6% include gendered attacks targeting the individual’s religious beliefs, ethnicity, or sexual orientation. Around 10% are categorized as behavioral attacks, including baseless claims of alcoholism and late night partying, which is socially stigmatizing and damaging to reputations. [Note: a single post may fall into multiple categories.]

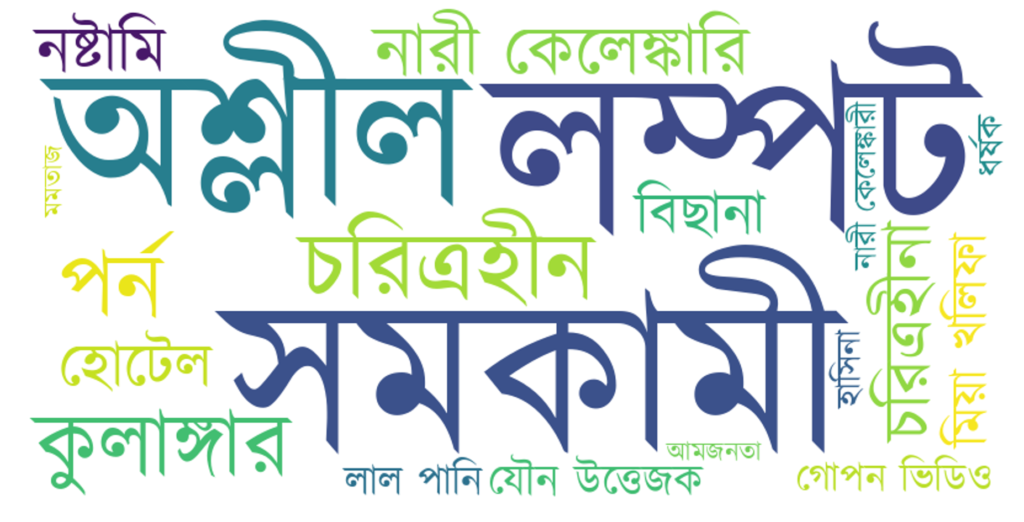

The above figure highlights a list of keywords that we found to be most associated with malign narratives on Facebook. These were used mostly against women with a smaller percent against gender-diverse and male political and/or public figures. We defined political and/or public figures as politicians, political candidates and immediate members of their families, as well as journalists, activists, and social media commentators with a public-facing political or partisan presence on Facebook and other platforms.

The most used Bengali keyword in an abusive context is shamakami, which translates to homosexual or gay. While it is an innocuous term on its own, it is used extensively to demonstrate a lack of strength, specifically traditional masculine characteristics, and defame politicians and public figures. Of note is that Section 377 of the Bangladesh Penal Code criminalizes “carnal intercourse against nature,” which is widely understood as the criminalization of same-sex sexual activity between consenting parties,making the use of the term not only defamatory, but exposing the targeted individual to serious bodily harm, especially if they belong to a smaller, sub-regional political party, or seen as a political dissident.

Interestingly, our analysis reveals shamakami was used to describe both political phenomena such as elections or the voting process, and political or public figures. In case of events, such as a shamakami nirbachon (gay election) indicated the uneven playing field in the country’s recent general polls, implying that politicians from the same party were competing against each other and that it was not fair. We excluded political events from our analysis — which was a smaller proportion of the analyzed content — and limited our findings to the derogatory use of homosexuality against individuals. Nonetheless, the rhetoric use of shamakami as a sign of protest underscores a tangible example of how political linguistics has evolved in Global Majority information environments.

For female targets, common slurs include “চরিত্রহীনা” (immoral), “নষ্টামি” (perversity), “মিয়া খালিফা” (referring to a former porn star), along with various derogatory terms for prostitutes. Most of the terms, if not all, convey an undertone of sexual depravity.

Male targets frequently encounter descriptions like “লম্পট” (lecherous), “নারী কেলেঙ্কারি” (women-related scandals), “পায়ু সৈনিক” (a pejorative term implying homosexual warriors), and “সমকামী” (homosexual).

Note: The total number of instances exceeds the number of posts, as some targeted multiple individuals simultaneously.

Unsurprisingly, women face these attacks more frequently than their male counterparts. Among the ten most targeted women, politicians from the BNP and the Awami League represent nine spots. In contrast, the list of the ten most targeted men features only two politicians, while the rest are mainly social media users known for explosive political commentaries.

The pages disseminating such content often display a uniform writing style or photo cards, sometimes recycling the same material in different formats.

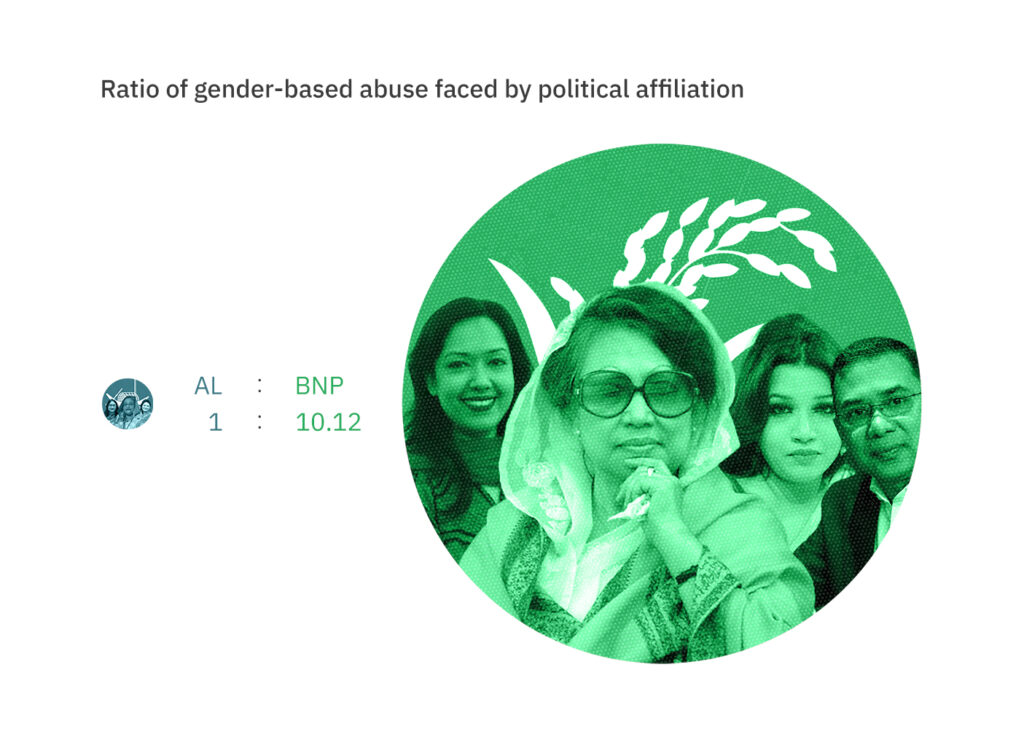

This analysis identified 51 shortlisted individuals, ranging from politicians and journalists to commentators and rights activists, targeted with gender-sensitive abuse 1,887 times in total. Members of the opposition BNP and their families experienced significantly more gendered attacks compared to those affiliated with the ruling Awami League. Individuals not known to support the ruling party accounted for 93% of the instances.

Specific individuals faced an exceptionally high number of gendered attacks. Tarique Rahman, a senior BNP figure living in exile in the United Kingdom, appeared in over 200 posts, accounting for 15% of the content reviewed. Posts implicating him are often linked with keywords suggesting scandal or immorality.

His daughters, who are not publicly active in politics, appeared in more than 150 posts. Along with Rahman’s mother, Khaleda Zia, the family were collectively subjected to 413 instances of targeted attacks, comprising 28% of the total posts reviewed.

Journalists and social media commentators were the subjects of at least 323 instances of gender-conscious attacks, making up 18% of the content analyzed. Tasneem Khalil, a Bangladeshi journalist based in Sweden, was mentioned in roughly 145 posts, with over 90% including homophobic slurs.

Shama Obaid and Rumin Farhana, notable female BNP politicians, faced nearly 345 instances of attacks, often with false claims about their personal lives, including alleged affairs with foreign nationals. They are known for engaging with foreign diplomats in Dhaka.

Sheikh Hasina, the long-serving female prime minister, experienced 45 gendered attacks, with some instances involving derogatory terms for transgender people. However, Hasina was also mentioned in a positive light in 223 instances, primarily in content targeting the ruling party’s opponents, journalists, and activists.

Our analysis reveals significant variations in the scale of attacks. Women politicians belonging to the BNP and its allies faced ten times more gendered abuse than their female counterparts from the Awami League. These attacks were predominantly focused on their personal lives, often with sexual undertones, with the intent of damaging their reputation.

We find further evidence of altered videos and images, as well as deepfake pornographic videos, of several female party members from the BNP in the lead-up to the election and cross-posted on TikTok, Telegram and Instagram, in addition to Facebook. Deepfake pornographic videos —often without audio or captions—featuring notable BNP female politicians however only comprised a very small percent of the overall altered and edited digital media landscape Majority of malign narratives featured poorly edited videos or cropped photos of politicians carrying alcohol or found in salacious positions.

Over 700 Pages falsely claimed to be news or media organizations and representing social or community organizations. Only 137 Pages acknowledged a political affiliation without clear disclosure of the associated party. Both on Pages and Groups, there was often a deceptive portrayal, such as posing as opposition supporters but sharing content to the contrary. This is consistent with our previous findings that demonstrate a lack of transparency on Pages and Groups that falsely represent news or community organizations, however, are political actors sharing hyper-partisan messages. In addition, we found impersonating Pages and Groups that use a political party’s name or symbol despite having no affiliation with them, and share misleading information to confuse constituents.

We find that a select network of Groups and Pages share the same abusive content within seconds of sharing the first content, including reuploading, to establish a carefully crafted malign narrative. We also find that the majority of abusive gendered content targeted at political figures originates from these pages, indicative of a centralized operation.

Our fact-checkers determined that nearly all the posts contained false information, thus qualifying at least as misinformation and often veering into the realm of disinformation. They also found that the vast majority were shared by pages and groups actively promoting content supporting the government and the ruling party.

Understanding the gendered and sexual dimensions of abusive speech, particularly in the context of seemingly neutral terms like “gay” and “homosexual,” requires a nuanced grasp of language intricacies and their contextual implications that extend beyond their literal, surface meanings. In Bangladesh, these terms are weaponized to denigrate men perceived as effeminate, undermining their gender identity and orientations while reinforcing harmful stereotypes. Likewise, referring to female figures, such as politicians or journalists, as “Mia Khalifa” serves as a tool for slut-shaming or casting aspersions on their perceived promiscuity. In both cases, the language used not only perpetuates damaging stereotypes but also contributes to a culture of misogyny and homophobia.

Existing laws of Bangladesh provide frameworks for evaluating gender-sensitive abuse, gendered attacks, and sexualized assaults. Several statutes — chiefly amongst them the Cyber Security Act, 2023, the Pornography Control Act, 2012, and the Penal Code, 1860 — criminalizes misinformation and disinformation as well as expressions that are offensive, intimidatory, defamatory, or blasphemous. Moreover, the Women and Children Repression Prevention Act, 2000 and the Children Act, 2013 impose certain restrictions on content depicting abused women or children in conflict with law. Notably, these restrictions are permissible within the broader constitutional exemptions for “decency,” “morality” or “defamation” under Article 39 of the Bangladesh Constitution.

However, while the laws are sufficiently broad to address abusive content, they are rarely invoked, either because such attacks are considered insignificant or because the authorities refuse to take complaints seriously. Opposition figures and dissidents face significant challenges in filing cases with law enforcement agencies and before courts. Even when cases filed by them are taken into cognizance, experts interviewed say they are more likely than not to be dismissed, especially if the attacks are orchestrated by individuals associated with the ruling party. Most cases filed under these laws, particularly under the recently repealed Digital Security Act 2018, have been initiated by individuals affiliated with the ruling party. Additionally, the biggest obstacle in filing cases against gendered and sexualized attacks is that victims often have to bear the burden of proving that the allegations are not true, which, for a public figure, can turn into a media spectacle and have a Streisand effect.

Meta’s hate speech policy prohibits various forms of slurs, dehumanizing speech, harmful stereotypes, or expressions of contempt or cursing based on protected characteristics, such as sexual orientation, sex, and gender identity. For instance, content containing genitalia or anus references , profanities , or sexually derogatory terms (such as whore, slut, and perverts) is prohibited.

Similarly, Meta’s bullying and harassment policy adopts a broad approach, acknowledging diverse manifestations of such behavior and the significance of context and intent. It follows a convoluted tiered system offering varying levels of protection for different user categories, with non-public individuals, and especially minors, enjoying heightened protection, while public figures are shielded primarily from the most severe attacks. Universal protection is guaranteed for content containing severe sexualized commentary or images, unauthorized sexualizing an adult or minor, or derogatory sexualized or gendered terms (like whore and slut). Additional safeguards extend to individuals subjected to claims about sexually transmitted infections, gendered cursing, or statements undermining physical appearance, though adult public figures can only enjoy the protection if they are “purposefully exposed” to the content. Furthermore, certain user groups — including private minors, private adults, and minor involuntary public figures — can self-report and access further protection against targeted harassment based on sexual orientation, gender identity, romantic involvement, or sexual activity. Meta also considers specific contextual factors when taking action, such as mass harassment directed at individuals at risk of offline harm (such as opposition figures, government dissidents, and human rights defenders), or state-affiliated networks targeting individuals based on protected characteristics.

However, under both these policies, Meta faces significant challenges in discerning between statements of fact or critical commentary and outright attacks or abuses. This difficulty is compounded by factors such as language competence and a lack of local contextual understanding, which may hinder the platform’s ability to accurately understand the intent behind the language used, recognize vast diversity in how offensive content is expressed and perceived, and effectively identify instances of gendered and sexualized attacks, which can often involve subtle, coded, misspelled, or context-specific language. Reliance on the context and intent behind the content can be challenging to accurately assess with automated systems, especially in scenarios where distinguishing between harmful speech and benign usage of similar language often requires nuanced understanding. Attackers often use sophisticated tactics to evade detection, making it difficult for the platform to protect individuals effectively, especially those at heightened risk like opposition figures and human rights defenders. Altogether, these impact the consistent enforcement of these policies, as biases, both algorithmic and human, coupled with resource constraints for non-English speaking regions and smaller markets like Bangladesh, can affect effectiveness and reach of enforcement efforts.

Furthermore, while offering protection for the most severe attacks against public figures, this distinction can be problematic as public targets can still face harmful and pervasive harassment that does not meet the threshold for severe attacks but nonetheless has significant negative impacts. Moreover, requiring targets to self-report means that individuals need to recognize and report harassment themselves, creating a burden on victims who may not always feel safe or empowered to report incidents. Ultimately, these complexities underscore the necessity for more robust, context-aware approaches to effectively safeguard users against gendered and sexualized attacks.

Bangladesh’s Digital Security Act

Appendix

Abbreviations

How data were labelled:

Sheikh Waheed Baksh3

Apon Das3

Manisha Biswas3

Fowzia Afroz3

Subinoy Mustofi Eron3

Shahzeb Mahmood3

Dhara Mungra4

Veer Pariawala4

Raghav Jain4

Aditya Surve4

Swapneel Mehta4

Shoeb Abdullah5

1 Hasan, M.R., Ahasan, N. (2022). The Win–win Game in Politics? A Study on Student Body of the Ruling Party in Bangladesh. In: Ruud, A.E., Hasan, M. (eds) Masks of Authoritarianism. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-4314-9_5

2 We eliminated the reference to individuals tied with rural units of a political party, for example, or incidents that exhibited signs of intra-party disputes.

3 Tech Global Institute

4 SimPPL

5 Independent Researcher

Data visualization by Sheikh Waheed Baksh, Dhara Mungra and Subinoy Mustofi Eron. Graphic design and illustration by Shafique Hira.

Copyright © 2023. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License unless specified otherwise.

Developed by SMS iT World